There are different pairs of hanging sneakers on the power line visible from Perry Street to UN Drive, a short distance from the police barracks and a kilometer from the National Police headquarters.

Millions of dangling sneakers are seen in cities and communities such as Monrovia, Paynesville, Duala, Matadi, and Barnesville.

But what’s the deal with all these dangling sneakers? It appears that a gang member is claiming territory.

“It is hung on the power line for strangers in the environment to know that there is an illegal substance; John, not his real name, is one of the gang leaders.

Liberia is dealing with an ongoing and devastating pandemic. The country is racing against the clock as many young people succumb to addiction. According to UNFPA, 2 out of every 10 Liberian youth are drug users.

The Liberia Drugs Enforcement Agency is the government agency policing the country’s drug trade. Michael Jipply, a communication officer, said it is challenging to eliminate traffickers since community members do not assist.

He believes that communities are protecting these persons because, in many cases, when there are traces of sneakers on electrical lines, communities refuse to cooperate with state security.

Though Jipply blames the community for not speaking up,people’s lives are being jeopardized by traffickers and end-users of these substances in places where they are sold.

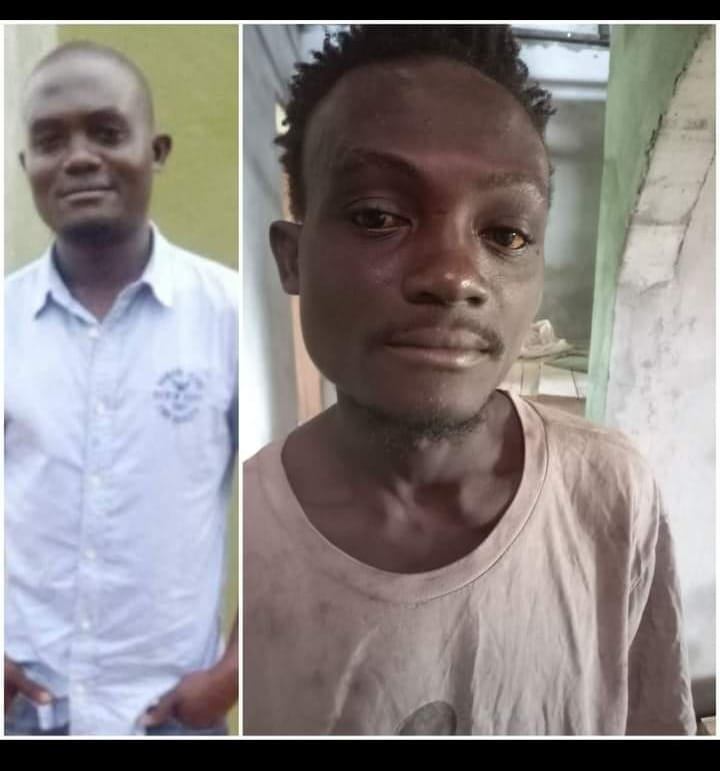

Cephus Tweh-Jlay has a 19 years history of substance abuse; before his addiction, he played professional football.

Jlay was exposed to drugs by a second-division goalkeeper he regarded as a soccer mentor.

“He give me opium and later introduce another drug that he said will make me be excellent in the goalpost”” he said.

Jlay played alongside soccer players such as Anthony Snorti Laffor but left the sport after being addicted to narcotics.

Like Cephus, Richlieu started in high school with a friend whose parent was a drug seller.

He said his parents changed his school to a mission (boarding) school, but he still needs to change.

“I began using marijuana in high school, but my parents believed that transferring schools was the best way to curb my habit,” although it was difficult.”

Cephus and Richlieu are alumni of the Liberation Center, a faith-based institution run by Sam Nunoo and partners to help addicts.

Nunoo said for addicts to recover fully, they need to accept willingly.

“We have had an experience that family brought their son for recovery, but it was difficult, the person ran away, so you can’t push addiccan’t change, it has to meet their consent.”

Cephus, Richlieu, and others are baptized and are now activists against substance abuse in several communities.

We accompanied Cephus to some of the ghettos earmarked by the dangling sneakers.

In Fear water, located in Duala, we met Cecilia; she relocated to this place because prices in Brewerville are high.

She has been on substance abuse for over two years. “The price in Brewerville is expensive and I used Coco and Taa, the only way I can purchase it is by men sleeping with me.”

Cephus’s advocacy has yielded results; his maternal cousin, Tina, spent 17 years in the ghetto.

“My kid brought his uncle (Cephus) to me, and then I told myself it’s time for me to leave the ghetto,” she added, referring to her only son.

“I wasn’t sure at first when Cephus took me to the rehabilitation facility, but he encouraged me, and that’s how I am successful now.”

Young people are becoming hostages of substance abuse, increasing their vulnerability gradually. Monrovia housed many addicts: men, women, and even children.

The vast fallout from Liberia’s war includes a sector of the population damaged by and dependent on illicit drugs. And along with widespread drug use, production and trafficking hamper post-war recovery efforts.

To sustain their desire and use of narcotic drugs, these young people who live in ghettos, street corners, and cemeteries often resort to crime, including armed robberies.

“No way to make it; people do not trust us. They say we’re into the habit; if they do, we will steal from them,” said Paul, 14 years.

New Law on Drugs

The fight against illicit drugs in Liberia is challenging in an overwhelming context. Liberia passed its legal framework to address the issue.

The Senate divides drug offenses into non-bail and bailable, depending on the gravity of the crime, but how effective will the implementation be? As a result, traffickers and users may exploit the flaw.

Substance misuse is rising, producing health difficulties and increased criminal activity, impeding production, damaging relationships, enlisting social and moral standards and implying societal achievement.

Paul knows why a dangling sneaker is on the power line “The drug dealer is here; we know him, but we are afraid to speak before they harm our family or us.

“The drug dealer has a very strong support and it’s spoiling the community, there is a need to carry on a massive shoes removal in these communities and implement the law.”

Production

The drug problem in Liberia extends beyond consumers.

According to the Liberia Drugs Enforcement Agency (LDEA), farmers are tempted to produce cannabis rather than other crops since the revenues are more significant, and they can transport the substance simply throughout the region.

“Local farmers in Bong and Nimba counties (100 and 150 kilometers from Monrovia, respectively) are continually planting these drugs for regional trade.”

Marijuana is now an increasingly popular cash crop. Within three months, farmers see profits versus seven years for rubber or three years with palm (ingredient for oil).

Much of Liberia’s cannabis is grown in southern Liberia or trafficked in from Sierra Leone, Guinea, and Nigeria, according to the LDEA.

LDEA reported US$100 million worth of cocaine placed in a container bound for Monrovia;but the defendants pleaded not guilty

Colds, malaria,TB, and uterine infections in women are among the most common illness concerns among drug users living in ghettos, according to a research titled Social and Economic Impact of Illicit Drugs. Other diseases include gonorrhea, syphilis, and hepatitis.

At-Risk Project, Fiasco?

Months after the Liberian government and its partner launched a National Fund Drive for the Rehabilitation of “At Risk Youth” in Liberia, “5 At-Risk Youths recently attended detoxification and rehabilitation programs, but critics believe it is a gimmick.

There needs to be a plan to rehabilitate the Vulnerable youths of Liberia as stipulated in the ” Pro-poor Age”a for Prosperity and development. The PAPD is a complete scam, said Thomas Brown.

“This government has grown entirely hostile to aspirations in its attempt to impress the populace by fixing problems.”

Odecious Mulbah, a social activist, said, “If this administration is unwilling to give entirely to the country’s young people, she should refrain from mocking them and causing negative consequences in her pursuit for popular support.”

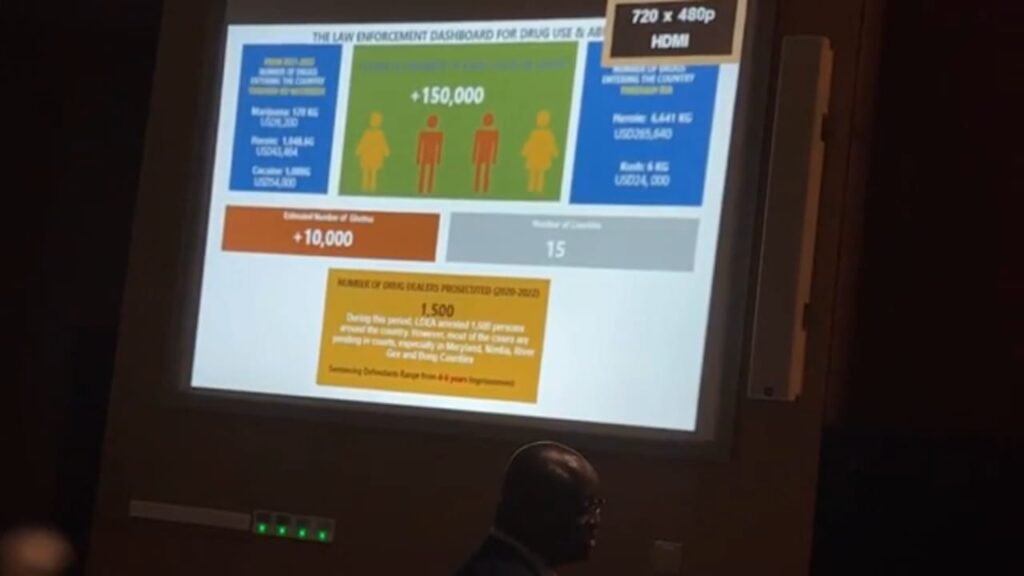

The Minister of Youth and Sports, Zeogar Wilson, at the National Fund Drive, put the number of at-risk youths in the country at 150,000, claiming they are primarily found in the estimated 10,000 ghettos throughout the country, with Montserrado County leading the list.

Following initial delays in adopting the project, he stated that the cabinet adopted the project in February 2022 in a meeting with the President.

There are four thematic areas, including creating an enabling environment for youth, training and recruitment, sports and recreation promotion, and social protection, but it is yet to be implemented fully.

Watch out for the full documentary.

By: Maima Wright